Russia is huge. We all know that. And yet, pretty much the entire North of Russia is nearly empty. That’s especially clear in Siberia, with almost all of its population concentrating in a narrow stripe across the southern border, similar to Canada.

That sounds obvious and even pre-determined. Wouldn’t people naturally flock to where it’s warmer, sunnier and more fertile?

And yet, that’s far from obvious. Very recently Russia used to be much colder and much more northern country with its most productive, advanced and richest population living far north. In fact, just 350 years ago pretty much all of Russian taxpayers used to live in the towns of Arctic region.

Russia moved south very recently. It’s current configuration was established only circa 1900 with the construction of the Trans-Siberian railway. And the previous configurations looked very, very differently.

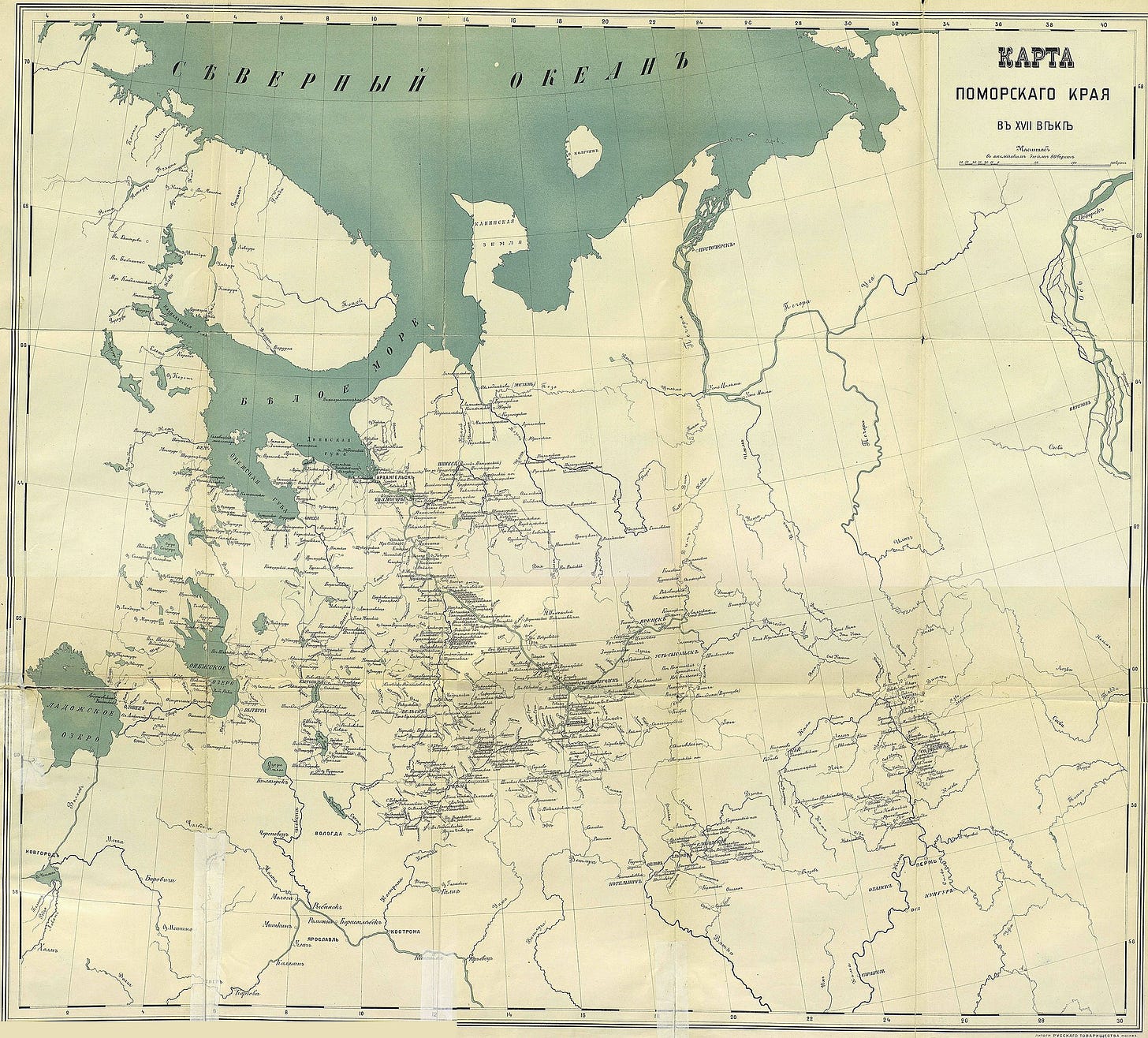

Let’s look at this map. It shows the main communication lines that historically connected the European Russia with Siberia since circa XII century till nowadays. How did it change over time?

As you see on this map, original, medieval routes lied very far north, in the Arctic and Polar Urals. Novgorodean expeditions to Siberia all went via the sub-Polar rivers. Much later, around 1600 communications moved south and the early modern route was established. Via these middle river routes Russians colonised Siberia, reached the Pacific coast and crossed the ocean to settle in Alaska. Only around the year 1900 construction of the new Trans-Siberia railway once and forever shifted population and the economy south, leaving the old northern strongholds to poverty and desolation.

So for the past centuries Russia has been continuously moving south. That makes sense - once again, south is warmer, sunnier, more fertile. But why did Russians go so far to the North in the first place?

Let’s go a bit deeper in history.

Slavs who colonised what is now central Russia in the Middle Ages were first and foremost a river civilisation. In Balkans, in Central Europe, in Russia, Slavs always settled around the rivers.

River was a source of water. A source of food. In fact, until the 20th c most of protein Russian peasants were getting was the fish protein. Orthodox Church considered 170 to 210 days out of 365 to be the fasting days when you were prohibited to eat meat or dairy. But you absolutely could east fish.

River was also a source of communication. People overwhelmingly travelled and traded via rivers. During the summer - on boats, during the winter - on sledges. There were not so many roads apart from the river network and those that existed were usually viable only for the winter time (when all the dirt, mud, and swamps just freeze).

If a river way was uninterrupted, that was great. That meant you could just put your freight on a boat and send it downstream. Like these huge wooden ships, belyanas, used to be sent from forests of Upper Volga to the deserts of the Lower Volga at negligible cost. You just had to go with the flow, downstream, and that’s it

But what if the river way was interrupted? What if you need to get from one river to another, rivers being the only real lines of communication?

Well, then you need to do a portage, “volok” from one river to another. In more settled, old colonised land it meant carrying goods from one river harbour to another. That’s why Russia has toponyms like Volokolams, Vishny Volochek, Nyzhny Volok and so on - these are all locations of old portage lines between river basins.

In less developed lands and during the far-away expeditions you had to literally carry the boats and the goods on you back. Which of course limited both the size of the boats and the weight of the goods you could take

But what goods would you ship down the river and carry on your back during the portage? Not much really. Russia was poor.

It was poor food-wise: most of Central Russia where Russian people lived back then, lied in a zone of boreal forest with rather infertile land. You know how is the old, Central Russia called in Russian language? Нечерноземье. Which means - Not Black Soil. All of significant Medieval Russia cities - Rostov, Vladimir, Suzdal, Yaroslavl, Tver, Novgorod, Moscow, Smolensk, they called liked within Not Black Soil area.

And yet, existence of Not Black Soil implies the existence of Black Soil, Черноземье. Indeed, down south, there lied some of the most fertile lands in Europe. You just had to cross Oka river. However, they constituted the “wild field” inhabited by the steppe nomads who of course wouldn’t allow farmers to settle there. It was a historical paradox of early Russia: Russians practiced agriculture on soils poorly suited for agriculture. Meanwhile, far better soils of the south were beyond their reach.

Russia was poor resource-wise. It didn’t have sources of good iron - only the poor-quality bog iron. No sources of precious metals either. Whereas it had lots of forests exporting it from the hinterland presented problem even in the 18th c, let alone in the Middle Ages. Before the construction of St Petersburg and a system of canals connecting it with the hinterland, Russia wasn’t really able to export the bulk goods. It didn’t have much to export to fund the purchase of armaments for its imperial expansion.

Or did it? In fact there were two goods that could be easily produced in Russia and then exported.

First, slaves. Pre-Mongol Rus was the major exporter of slaves in Medieval Europe. In a sense, Pre-Mongol Rus was very much alike some West African kingdoms like Dahomey or Benin, greatly surpassing other competing slave-exporting polities for example in what is now Czech Republic. I’ll certainly cover it in one of my next blogposts on the White Slavery.

And yet, the Mongol Conquest destroyed the old Rus and cut off what is now Russia from the really lucrative Mediterranean slave markets. Of course, chattel slavery existed in the North Europe, too. Even in the 14th c German merchants would visit Novgorod to “buy girls” (девкы купити). But northerners had less cash and by the late Middle Ages chattel slavery was on decline here.

Secondly, furs. Unlike the demand on slaves, the demand on furs was booming in the Northern Europe, too. And Russian states could provide a lot of them. The problem was that they would hunt all the valuable animals extensively and literally to the extinction. Thus they had to move in their search for sables and beavers further and further (All the way to Alaska).

The medieval polity that benefitted the most from this fur trade was the Novgorod Republic. This northwestern city-state dominated the huge hinterland, and had a regular connection with Europe, where it exported it goods.

Novgorod was always regarded as a sort of a historical paradox. First of all, its obviously republican constitution with its prince being more a hired mercenary than a true ruler set it apart from other Russian states. Second, its bourgeois social order and proximity to the West was either cheered or loathed by thinkers of the future, depending on their general political stance.

In neither of these respects however, Novgorod was too much of an anomaly. It was a republic indeed, but it was considered problematic only by the historians of the imperial age. Imperial historians would not only justify the monarchic order of Russia but would claim it has always been purely monarchical. When they could not ignore “exceptions” like in the case of Novgorod, they simply declared them anomalies. Recent research however, showed that republican institutions were typical for most of early Russian polities and only gradually fall to the usurpation by princes (see Froyanov).

Second, its role in the economic world-system was dual. It was indeed an overlord of a huge colonial hinterland which it exploited, taxed, draw resources from. But it was certainly a periphery to Europe. Yes, it traded with Hanse, but it was a trade with clear core vs periphery dynamics. Novgorod would sell raw goods, first and foremost furs. In return it would get manufactured goods. Hanseatic merchants would refuse to buy anything processed from the Novgorod sellers (even sewn fur coats), probably aiming to eliminate any potential competition in processing them. All of the export was done via European ships, Novgorod had no merchant navy of its own.

In relation to its eastern hinterland Novgorod was an undisputed metropoly. In relation to Europe however, it was a periphery, reduced to the relations of unequal exchange by the superior Hanseatic merchants. In this respect, Novgorod was not much different from the rest of the great Russian polities of the past and the present.

(Quite possibly, Soviet leadership purposefully tried to cleanse this pages from the Russian history. In the 1970s Soviets destroyed the ruins of the Gotenhof and the Peterhof, two Hanseatic factories controlling the Novgorodean exports, building the hotels on their sites)

It would be wrong to assume that Novgorod Republic was a unitary state. There was a dominant city-state of Novgorod, indeed. And there were vast lands with heterogenous population whose relations with Novgorod could vary. The second biggest city of the republic, Pskov, was Novgorod’s worst rival, constantly struggling for independence (much like Florence and Pisa). It would even side with Livonian crusaders trying to overthrow the Novgorodean domination.

Statuses of eastern territories could be very complicated. Some of them were city-states, subjugated to Novgorod. Others were principalities where Novogorodeans appointed their deputy-governors. Some were native tribes - Finnic or Uralic - whom Novgorodeans made to pay tribute or attempted to do so. They were not always successful. For example, one of Novgorodean expeditions to Yugra (medieval route to Siberia on my map) in 1197 was destroyed by the natives.

Along the White sea however, another subethnic group flourished, which was very superficially controlled by Novgorod authorities. They were called Pomors (поморы). Literally, the sea-coast-dwellers. They were seafaring people who launched independent expeditions eastward to Siberia, northward to Spitsbergen and would later play an important role in the Russian history. Their roots are unclear, though it’s obvious that they are the mix of Russian settlers and local Finno-Ugrics.

Those eastward routes through the Pomorye land, controlling the furs supply were instrumental for the Novgorodean success and made it the richest of all the Russian states. So that was where the rising Moscow made its first strike.

Moscow was initially a tiny and unimportant principality. It would gain importance however, when Muscovite princes started collecting taxes for the Golden Horde. They were not yet powerful, but they became rich. Having some cash, they started buying land, and doing it strategically - orienting mostly northward.

They tried to avoid unnecessary conflict attempting annexation of other powerful feudal principalities such as Tver, Rostov, Yaroslavl. Instead of that, they first concentrated lands around Moscow and then increased their political influence in the North.

How did they do it? Historical maps which cover huge territories in one colour often convey a very wrong image. Homogenous colour implies that it was a homogenous territory, kinda modern France, living by unitary law, standardised rules, and run by the same administration. Which is not the case.

Hobsbawm suggested a better metaphor. When we say ‘Muscovy’, or ‘Austria’, or ‘Brandenburg’, imagine that as ‘Duc of Bedford’s estates’. When we say that, we don’t imply that they comprise contagious territory or are run according to the same rules, or have the same legal status. The same way medieval or early modern realms were conglomerates of very diverse territories.

I would suggest even a better metaphor in my opinion. Early Muscovy was not so much a conglomerate of estates as a conglomerate of companies. That may sound as an exaggeration. But let’s consider the case of Vologda.

Vologda was a river port of immense importance controlling the river route eastward. Around 1350 it was under Novgorod domination. It was a city state with elected magistrates, citizen assembly (veche) and so on. But the supreme power belonged to the Novgorod deputy (наместник). In 1360s Muscovite forces come there and - no, they don’t annex it. Novgorodean deputy remains in a city, but now Moscow pushes in its own deputy, too. A couple of decades later Vologda levy already participated in a Muscovite expedition on Novgorod. By 1400 Vologda was a Muscovite province in everything by name. However, the formal annexation of Vologda happened only in 1471, after the final defeat of Novgorod.

What does it teach us about Muscovite strategy?

First of all, Moscow purposefully expanded north - to control the supply of raw materials (fur), the only tradable good it could get

Muscovite expansion was rather a chain of hostile takeovers rather than Lord of the Rings style battles. It didn’t invade and annex - it rather first pushed its representatives to the local government, imposing effective duumvirate, then expanded its power and authority, then took complete control and only a century later made formal annexation. Muscovite strategy was playing lowkey, in many iterations, with claims for status and prestige lagging far behind its actual growth of power and resources.

This created a sort of strategic problem with Muscovy temporarily becoming an uncontiguous state - sort of Prussia-Brandenburg. And yet, this situation was temporary. The blow on Novgorod however was fatal, it could never get over Moscow cutting it from the east. Export drained, cash drained, Novgorod became a relatively easy prey for the princes of Moscow. Only after cutting Novgorod from its eastern periphery and ways to Siberia they made coup de grace, finishing the ancient republic.

What would Muscovy do then? Well, expand further north. In 1499 Muscovite forces sailed down Pechora river and founded a fort of Pustozersk near the Arctic Ocean coast. To put things into perspective, while Russia was doing this Arctic expansion northward, its southern border lied on Oka river, few miles from Moscow. The bank of Oka was simply called ‘the Bank’ in Russian sources. Service on the Bank was the most hated one by the Russian nobility - hard, dangerous, constant fighting with nomads and not lucrative at all. Expansion to the Arctic wasteland with its harsh climate and terrain was so much easier than expansion southward.

And yet, the real rise of these Arctic territories commenced circa 1500. It was helped by two factors. First of all, in 1552 Russians destroyed Kazan. Kazan lied near the confluence of Volga and Kama rivers thus controlling both the traffic down Volga to the Middle East, and up Kama to the Urals. Kazan merchants monopolised these routes, acting as an intermediary. Moreover, during every Russo-Kazan War which lasted from 1439 to 1552, Kazan would block the traffic for the Russian goods completely. Which means Russian had no access to the Caspian and thus to the Middle East at all, while the route to the Urals was very long, round-shaped and suboptimal.

In 1549 the last real ruler of Kazan - Safa-Giray dies (While early Kazan Khans descended from the rulers of the Golden Horde/Kipchak Khanate, late Kazan Khans were a branch of Girays from Crimea). He was succeeded by his three years old son Utamesh-Giray with his mother Soyembike as the regent

With both threat of force and bribes, Ivan IV of Moscow pressured Kazan to extradite them two to Moscow and put his own puppet Shah-Gali- a ruler of the vassal Qasimov Khanate as a Khan of Kazan.

On next iteration, Ivan pressured Kazan to give him all the ‘Mountain’ (=right bank of Volga), part of the country. The Qurultai assembly acquiesced again. On the acquired land Ivan IV built the fortress of Sviyazhsk - on the island in the middle of Volga - just few kilometres upstream from Kazan. Later it would serve as the main logistical base during the Siege of Kazan.

And finally Ivan sent to Kazan his governors, abolishing even the formal independence of state. Only at this stage locals raised a rebellion, ousted Shah-Gali and started preparing for defence. Which was pretty hopeless by that point as Muscovites had a ready base just few kilometres from the city. After 40 days Kazan fall, city destroyed, population slaughtered and the entire Tatar population ousted from the river banks deep into the hinterland

You still see it on the maps by the way. If you look at the modern ethnic map of Tatarstan, you’ll see that pretty much the entire population around the rivers is Russian, while Tatars live deeper inland. That is mostly the result of that ethnic cleansing of 1550s.

What does this story teach us? Again - Russian expansion was often not so much an open aggression from the very beginning as a kind of hostile takeover, done via many iterations, with the use of force, bribes, soft power and so on. The goal was to impose the real authority over the country. It was done by bringing up new and new demands each of them presented as the last one. This lowkey game was so effective that Kazan didn’t raise any effective resistance until it was too late.

Another lesson is the importance of river communications for the Muscovite expansion. Forces and ammunition for the siege were shipped via the river, the main logistics base was located on the river, too. After the siege, local population was deported from the river, living it to Russian settlers who now took effective control.

This war not only opened the entire Volga to Russians, thus allowing them to establish direct communications with the Middle East without any intermediaries, but also allowed Moscow to cut off a route to the Urals. While previously communications with Northern Urals were solely done via long northern river routes with many volts, now trade with Upper Kama became very easy. You could simply sail from Moscow via Moskva, Oka and Volga downstream and then turn to Kama soon after passing Kazan. You could just sail upstream via Kama and reach Urals.

This new easiness of a route triggered the unprecedented rise of the Stroganovs about whom we are gonna talk very soon.

Another event determining the socio-economic and political fate of Russia was the discovery of the way to Europe.

We all know of many powerful and rich European colonial companies. British East India Company controlling the Indian subcontinent, Dutch East India Company controlling what is now Indonesia and Malaysia and so on. We certainly associate these companies with southern seas, spices and plantations.

And yet, these were relatively new ones. The oldest of such colonial companies was the English Muscovy company.

How? Well, it’s a long story. In the 1550s the English were desperately looking for the trade routes to Asia. Old routes via the Cape of the Good Hope were occupied by the Portuguese, so English tried to find a northern maritime route to China. They sent an expedition to sail around Scandinavia all the way east.

England was a pretty sorry maritime power back then with little expertise and little institutional capacities. That’s why they appointed an Admiral with no naval experience - Sit Hugh Willoughby. Willoughby was a knight, a good cavalry commander and could get a naval commission only in a purely continental power (which England was).

Fortunately for the English, they were in close alliance with Spain, a real naval superpower. Spanish expertise was what raised England from obscurity. Most importantly, a chief cartographer of Spanish Casa des Indias Sebastian Cabot worked in England and prepared a generation of young captains with real training. They were first capable seafarers England had.

One of them was Richard Chancellor - a disciple of Cabot. He was appointed as a captain of one English ships for his expertise. Very soon storms drifted the ships apart. Genius Willoughby got lost and decided to spend a winter on the Arctic shore, on Kola Peninsula. Of course he froze to death with his entire crew.

Richard Chancellor however, sailed south. He entered the White Sea and soon reached its Summer Coast (summer coast = no ways to get there except in summer). There he met local Pomor fishermen who explained him that he is not in China, but in Muscovy. They introduced themselves as English envoys and Ivan IV invited Chancellor to Moscow.

Ivan was absolutely happy to see Chancellor. A big problem of Muscovite Tsardom was that it had no seaports at all. Yes, it had Novgorod, but Novgorod was located inland. From Novgorod you had to ship down Volkhov to the Ladoga lake, cross it, and then ship via Neva to the Baltic. Sounds good?

There are two problems. First of all, it means that you need to ship goods from Novgorod to the sea by small river boats. Which of course can’t sail far in the open sea. So you need some sea port to unload river boats, upload their freight to the bigger sea ships and thus export stuff.

The Neva delta would be a natural spot for that. And yet, this ‘rotten swamp’ as it was called by local Finnics was a terrible place to build a city. Marshy terrain, cold and wet climate. Any settlers were dying like flies, even living here was arduous, let alone building a city in these god forsaken marshes.

Peter I would succeed with this task at enormous cost both regarding cash and human lives. But Old Muscovy simply had no resources for that. Therefore, it largely had to trade with the West through Polish or Livonian intermediaries. Which was problematic. First of all, frequent wars closed these routes for Russian commerce. Secondly, Poles and Livonians both considered Russia as a potential threat and thus censured any imports to Muscovy, prohibiting to ship there guns, gunpowder or any sort of weaponry, rightfully concerned they gonna be used against them. And yet, Moscow needed this exact stuff to use it against Poland and Livonia. Which would naturally not allow that.

What could Ivan do? The arrival of Chancellor was literally the blessing of God. Ivan accepted him in Moscow, and gave him a right to trade with Muscovites freely and without any taxes. Chancellor returned to England and presented his new privilege to a new queen Mary Tudor. That’s how the Muscovy Company, the earliest of English colonial companies was established.

Here you see the Old English Court straight across the Kremlin - one of the oldest civilian buildings of Moscow.

Thus Ivan commissioned to build a first Russian seaport in Arkhangelsk. This place had a natural harbour good enough to accept large ocean ships. And direct trade with Europe via Arkhangelsk started booming.

To put it in other words, in 1550s northern, Arctic part of Russia, got a jackpot. It got both the direct access to Siberia via the northern rivers and direct access to Europe via Arkhangelsk. Very soon Pomorye, the Land by the Sea, became the wealthiest and the most economically important part of Russia. It controlled both river routes allowing to obtain tradable goods and maritime routes allowing to export them.

That sort of gives context to what a major historian Kluchevsky characterised as ‘the most unexplainable event in Russian history’ - establishment of Oprichnina. In 1565 Ivan the Terrible divides his country into two zones: Zemschina (=the Land), and Oprichnina (= those set apart). Zemschina remained under the control of regular aristocratic institutions - most importantly of the Bojar Duma. Meanwhile Oprichnina was personally run by Tsar Ivan outside of the framework of any ancient established institutions.

Oprichnina hosted oprichniks - the first political police in Russian history. Marxist historians argued that oprichniks came from minor gentry whom Ivan used to undermine the power of great aristocracy. Later quantitative studies showed it wasn’t quite true: in fact a number of ancient powerful families also joined oprichnina.

Those joining the number of oprichniks had to take the following oath:

I swear to be true to the Lord, Grand Prince, and his realm, to the young Grand Princes, and to the Grand Princess, and not to maintain silence about any evil that I may know or have heard or may hear which is being contemplated against the Tsar, his realms, the young princes or the Tsaritsa. I swear also not to eat or drink with the zemschina, and not to have anything in common with them. On this I kiss the cross

Oprichniks waged a mass terror against Zemschina, wiping out any forces, families, individuals, Ivan could see as a potential threat. A number of prominent Bojar families and uncountable number of commoners were killed as result. This also included a cousin of Ivan, Prince of Staritsa, whom many considered to be a potential alternative to Ivan.

The most well-known purge was the massacre of Novgorod. After Ivan was informed that Novgorod nobility allegedly conspired against him, he came there with his oprichnik forces. They slaughtered Novgorodean aristocracy, magistrates, merchants, many clerics and did and indiscriminate massacre of townspeople whom nobody really counted.

Ivan spent little town in Moscow, moving to Vologda. Here he built a new stone cathedral, a huge castle for himself, moved here his treasure and administration and run entire Oprichnina from this new capital.

It makes no sense, does it? But let’s look at the map of the lands taken into Oprichnina

As you see, pretty much all of Oprichnina zone overlaps with Pomorye. On the one hand, these inland waterways cover the route to Siberia (orange). On the other, the seaport of Arkhangelsk allows to export them to Europe. In addition to that, a southern exclave of Stroganoff dominions secures the only alternative route to Siberia, though undeveloped yet. These were the territories Ivan decided to take under his personal control.

This is very symptomatic for most of Russian regimes. Discussing how Russia is governed we talk a lot about politics, ideology, religion. And yet, we pay too little attention to the economy of power. Russian regimes typically focus on two tasks:

Producing tradable goods (=raw materials)

Exporting them

This was certainly true in Ivan’s case. From his Vologda capital he controlled the flows of the main tradable goods he had, the furs, and via Arkhangelsk he could export them. This is also true of modern Russian regime which also pays huge attention to extracting natural resources and to maintaining and expanding transport infrastructure necessary to ship them.

That might explain an interesting phenomenon. Whereas many Russian institutions are highly dysfunctional and Russia really struggles with producing anything tradable, there are some working perfectly. For example, railways. Russian railways are exemplary, far surpassing probably all of the Western ones in their quality and reliability. They nearly always come in time, no matter the weather, natural conditions and so on.

Why? One answer is - because it is *the* priority. Reliable railways are necessary to exploit the inland resources and to ship them to seaports. That means the higher-ups really care about this institution and will make sure it’s functional. Meanwhile, less functional institutions are simply unimportant and left to rot.

Anyway, 16-17th cc were the age of glory for Pomorye and for the Russian North. Controlling both the routes to Siberia and the only access to the ocean Russia had, Pomorye grew very rapidly. It was the richest part of Russia, the only one which had virtually no serfdom but had instead a large middle class. They stereotypically lived in huge wooden houses, far bigger than tiny peasant huts of Central Russia

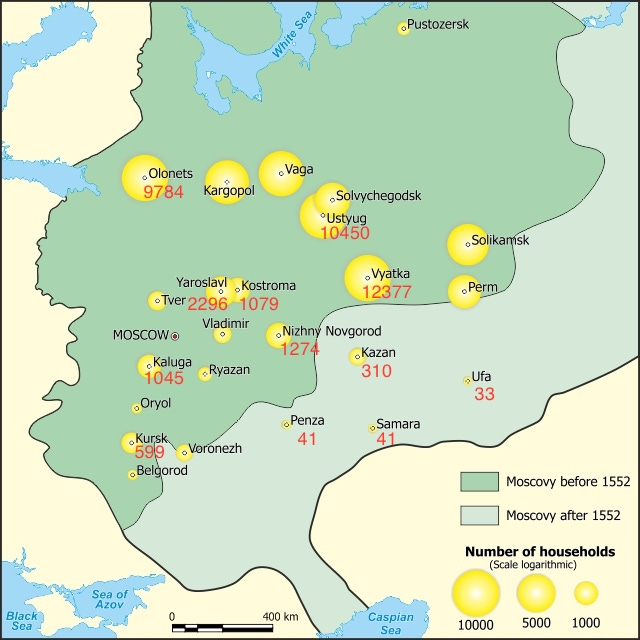

Let me give you an example. In 1682-1683 Moscow levied a musketeers tax, стрелецкие деньги, on provincial cities. For that purpose it assessed the number of tax paying households in each of them. I want stress that this is not the population assessment, that’s simply the assessment of personally free commoners (most of Russians used to be serfs back then) who were rich enough to pay the full share of a direct tax.

So what were their assessments?

As you see, sub-Arctic towns had huge taxpaying population. 12377 in Vyatka, 10450 in Ustyug, 9784 in Olonyets. Towns of Central Russia had much fewer taxpayers. Yaroslavl - 2296, Nizhny Novgorod - 1274, Kostroma - 1079. Southwest, the Slobodskaya Ukraine conquered from Lithuania in 15th c was relatively populated with Kursk having 599 taxpayers. Kazan, the capital of once independent Khanate had fewer - just 399. Meanwhile Penza, Samara and Ufa were just border forts in a newly conquered land with minuscule taxpaying population.

Nowadays Russia is unrecognisable. Former economic powerhouses of the North are destitute and often depopulated. The once glorious Vyatka (now Kirov) is a zone of permanent socio-economic depression. Meanwhile southern cities of Ufa or Samara turned into powerhouses: Samara now actually has the highest industrial output per capita in all of Russia.

Why? Because communication routes shifted south

In the 17th c old Northern routes were still important. They gave both access to Siberia and to Europe, securing both deposits of raw materials and the routes of export. And yet, after the establishment of St Petersburg, Russian trade shifted into Baltic. In fact, Peter I simply prohibited trading with the West otherwise than through his new Baltic capital. Of course, Pomorye started declining.

Moreover, routes to Siberia were shifting south to the red route. By the inland waterways Russians reached Tobolsk, which became the capital and the most important city in Siberia. Then Turukhansk, Yakutsk and finally Okhotsk.

Yes, counterintuitively it may sound, it was Okhotsk that was the first Pacific stronghold of Russia. It was founded in 1649 and by 1716 became the Russian Pacific base. Here the first Russian Pacific boats, then ships were built. From here they went to the Pacific islands and to Alaska which became the dominion of a Russian-American Company by 1799.

Meanwhile Vladivostok which we now associate with Russian Pacific present became Russian much later. Russia annexed these lands only during the Taping rebellion, exploiting the weakness of Qing Empire. A first fort in what is now Vladivostok was built in 1860, but it remained small and unimportant for very long. Most of communications with these lands were conducted through enormously long maritime routes. You can get the idea of their length and direction by how Russian navy went to the Russian-Japanese war

So how did Vladivostok grew important? Again, through the shift of communication lines. Russian leadership long contemplated of building a railway that would connect it with its Siberian outpost. The question was - where will we build it? This construction would shape the future socio-economic map of Siberia and of Russia in general.

In 1890 Alexander III gave an order to start the planning of a railway connecting St Petersburg with Vladivostok. Managers and engineers were debating where should the road lay. Some wanted to direct it north, through already developed and rich areas, primarily Tobolsk. Others argued that it should be built south, to exploit yet underdeveloped resources of South Siberia.

Eventually, the second option was chosen. Merchants of Tobolsk, the largest and richest city in Siberia were alarmed. They tried to offer enormous bribes so that the route would go through their city but in vain.

Trans-Siberian railway was the matter of extreme importance. It was also highly costly and posed many technical problems. Some believe the construction can go for many decades. In order to make it smoother, the Minister of Transport Vitte organised a special Siberian Committee to oversee the railway and gave it to the heir apparent, future Nicholas II. That was a smart move. The more time Nicholas spent on it, the more effort invested, the more emotionally invested he became. He wanted it done ASAP and let’s be honest, nobody in Russian empire would dare to argue with the future Tsar. That secured both lobbying and funding for the project and in 1891 Nicholas personally opened the construction.

This new roads completely changed the socio-economic fortunes of Russia. All over the course of the road new demographic and economic centres mushroomed. Samara is an example of relatively old 16th c city whose importance increased because of the railway. Chelyabinsk was an unimportant 18th c fortress which started booming after the construction. The most striking case however, is Novosibirsk. It didn't exist before the railway at all. It was founded in 1893 as a camp for the construction workers

And yet, it soon skyrocketed to be the largest city of Siberia far surpassing the former glory of Tobolsk. The now third largest city in Russia never existed before the railway and certainly wouldn’t appear without it. Meanwhile older norther centres like Tobolsk declined.

But probably no region contracted quicker than the once rich and affluent North, Pomorye. Trade routes, commerce investments, bypassed this region. People were living to sunnier and more fertile regions. This process took more than a century and as a result, old Russian economic powerhouses of the North now lie in ruins

While new population centres are mushrooming in the Russian southern sunbelt. But that’s for another story.

Let’s summarise, which lessons regarding the Russian imperial strategy can we learn from this story?

Russian expansion is often described as a story of hard-won battles. But it was most importantly a story of hostile takeovers. Step by step increase our influence, push in our representatives and so on. There could pass a century between the establishment of actual control and formal annexation.

Somehow many observers presume that we can ignore the economic context of Russian expansion. They ascribe it to ideological, historical, religious motives. That might not be wrong. But this expansion is critically dependent upon technological import and thus can not proceed without a constant flow of export goods.

Therefore, maintaining these export flows is a matter of first and foremost importance for the Russian leadership. Their priorities are: to secure the extraction of natural resources, and secure their export to the West. Without taking this into account we can’t understand either Oprichnina, nor Putinomics. Basically we can summarise priorities of the latter as building seaports, railways and pipelines. Everything to secure the continuous export of natural resources.

On a meta-level, there’s one more lesson. For the past 500 years, Russia has been continuously moving south. Its economic centre of gravity has been shifting from the sub-Arctic first down south, across Oka, then further south-East, across Volga. In the future we should expect that it would go even further south, to the Russian sunbelt along the Krasnodar coast. Indeed, that’s what is already happening. But that’s again, for another story

Many thanks to Ivan Bogaty for funding this publication

I'm very much loking forward to this substack. Your twitter threads have been one eye-opener after another.

I've been reading your Twitter feed and trying to share it with others, but most of them don't have Twitter and don't want to sign up and don't know how to get around the blocking "sign up please" dialog box. It would be awesome if you could "unroll" all of your threads here.